Dearden and his clapper.

For decades now I’ve been waiting for someone to package an oversize picture-book called The Films of Basil Dearden. The 1970s would have been a good time for that, since Dearden died in ’71 (car accident), and this mid-rank British director was in need of appreciation. Great big coffee-table books about cinema were then much in vogue (Truffaut/Hitchcock, The Citizen Kane Book, Flesh and Fantasy). But now, in this current era of poorly designed, un-illustrated e-books, I’m not exactly holding my breath.

Dearden has had a fair, if marginal, reputation in America, but on his home ground critics have been dismissive, often hilariously so:

His films are decent, empty and plodding . . . [1]

Dearden typifies the traditional Good Director in the appalling performances he draws from good actors; and in his total lack of feeling for cinema. [2]

Basil Dearden will never join the frontline of British film directors. He won’t be canonised, nor does he deserve to be among “Britain’s Best,” alongside Michael Powell, Alfred Hitchcock or even David Lean. . . . A workmanlike and very British drudge. [3]

Why no love for our Basil? Too much “sociological seriousness” is one recurrent gripe. Dearden had a fatal attraction to mawkish exposés of such things as juvenile delinquency, homosexuality, and miscegenation. Typically he’d attempt a heartfelt plea for tolerance and equality, or something like that, but his direction tended to misfire. So what we get instead looked like prurience and sensationalism, or even the message that tolerance and equality are bad juju, best avoided. Dearden threw irksome ingredients into a film just to be edgy. Supposedly he is responsible for the first-ever interracial relationship in British film (1951’s Pool of London). There the race angle is minor and gratuitous, tossed in to add spice to a workmanlike but unexciting production. This theme stuck with him, so that in two of his later films the interracial business is at the heart of the story (Sapphire and All Night Long, discussed below) and leads, seemingly inevitably, to violence and/or death. The moral to these films thus appears to be that miscegenation is transgressive and dangerous—so don’t do it!

The other complaint about Dearden’s work is his versatility. His output ran counter to the faddish, if dubious, auteur theory. In the course of his fifty-odd films, he made hilarious low comedies, and high-toned caper films; along with sociological thrillers, dramas, police procedurals, science fiction, science-fiction comedy—an indecipherable thing with Kenneth More called Man in the Moon—and at least one David Lean-style historical blockbuster, Khartoum, that was praised at the time but gets little respect these days, mainly because top-billed Laurence Olivier clowns around in his role. In the 1960s as today, such a range of subjects was suspect in itself. In Dearden there’s just not enough sense of authorial vision of the kind you see in French New Wave directors, who often enough seemed to be making the same film over and over. Or, for that matter, the films of such British contemporaries as Carol Reed or Hitchcock, whose high-strung narratives had a recognizable look and feel.

If you look at Dearden films indiscriminately, you sometimes get the sense of a hack-for-hire. You imagine him wrapping one film, and moving on to whatever likely project someone handed him. For example, in 1957 he directed a delightful Ealing-style comedy called The Smallest Show on Earth, about a penniless young couple (Bill Travers and Virginia McKenna) who think they’ve inherited a lavish provincial cinema from a distant uncle. The movie house turns out to be a broken-down “fleapit” in the care of some ancient, incompetent retainers (Peter Sellers, Bernard Miles, Margaret Rutherford). After some low comedy and inadvertent arson, the couple sell the fleapit to the greedy rival whose movie palace just burned down; whereupon they pocket a small fortune, and head off to Samarkand.

Dearden followed up this screwball classic with something called Violent Playground (1958), which inhabits an entirely different filmic universe. Now we’re in the Liverpool slums, where a police detective (Stanley Baker) is trying to find the young delinquent who’s setting fire to buildings. The arsonist is none other than young David McCallum, six years before his Man from U.N.C.L.E. stardom. On the lam from the police, McCallum grabs a machine gun, flees to a school, holds a classroom of children hostage, and nearly kills the local priest (the ubiquitous Peter Cushing) by pushing him off a ladder. No happy resolutions here, no uplifting moral. The unintended takeaway isn’t that the welfare of the urban poor needs to be improved, but rather that bad people live in housing estates.

* * *

And this brings us up to Sapphire (1959), a beautiful if (yes) plodding police procedural, one of Dearden’s few color films of the era. A young woman is found dead on Hampstead Heath. A police detective (Nigel Patrick) does his job, and all kinds of surprises unfurl. The victim, Sapphire Robbins, turns out to be an improbably Caucasian-looking mulatta who recently had begun “passing for white.” She was due to wed an earnest, duffel-coated Cambridge student whose lower-middle-class (English) family seems to have no idea of Sapphire’s origins. Our detective spends much of his screen time unraveling how and why Sapphire managed to “pass,” which initially is as much a mystery as her murder. We learn that she cut her social ties to black lovers and friends, lest they give the game away. Sapphire may well have got herself pregnant in order to trick the Cambridge student into marrying her (though the script is too bien-pensant to dwell on that point). When the circumstances of her murder are finally revealed, we get a truly surprising and unexpected ending, one too good to spoil here. But the major plot twist in the drama is something we might not have guessed at the beginning, and that is Sapphire’s low moral character. This is one police procedural where it seems the murder victim deserved her fate.

Begun in late 1958, after the Notting Hill Riots, Sapphire was inevitably probed and praised for its wide-ranging and rather sympathetic exploration of the black community in London. The blacks here are not generally poor or badly done by; some are snobbish, well-to-do professionals. Yet, although it won a BAFTA Best Film award, Sapphire is reviewed today mainly as a well-meaning curiosity, a clumsy if well-intentioned social critique that “reveals the shocking intolerance of many in the white middle class.” But what it really shows us is that blacks who arrived in England after World War Two were outsiders with their own subcultures and needs, and who had little regard for white folks and their condescension.

Sapphire is one of four Dearden films that were bundled up on DVD by the Criterion Collection in 2011 and released under the heading, London Underground. This quartet includes Dearden’s other big race-themed movie, All Night Long (made in 1961, released 1962). All Night Long is a very different kettle of fish from Sapphire. The screenwriter had the idea of writing a modern version of “Othello,” substituting a black American jazz-band leader for the Moor of Venice. The character is named Aurelius Rex, which suggests the scenarist’s mind was on Thelonious Monk. However the tuxedo-clad, silky-smooth black actor here (Paul Harris) is more along the lines of Chico Hamilton from Sweet Smell of Success. Likewise the jazz we get is conventional nightclubby stuff of the era. It’s played in an elegant private performance space, with the musicians and male guests mostly attired in dinner jackets and under-collar black bow ties. Roger Moore in his early-60s TV role as “The Saint” would be very much in his element. Nearly everyone’s dressed in black and white, and—lobby card notwithstanding—this is most appropriately a black-and-white film.

“Rex,” as everyone calls the black jazz-maestro, is married to a tall blonde chantoosie who has retired from the circuit, since Rex doesn’t like sharing her with the public. One of Rex’s sidemen is a conniving drummer (TV’s Danger Man/Secret Agent star Patrick McGoohan, speaking an uneven attempt at American demotic). The drummer plots to steal the blonde singer away so she can front his own band. His ruse is to convince Rex that the blonde has been fooling around with the saxophonist. So the jealous Rex challenges his wife, nearly strangles her to death, and almost kills the saxophonist too, for good measure.

And that’s the story. It’s not much, and the Shakespearean analogies seem forced and perfunctory. Our Iago figure, McGoohan, is too nervous and chatterboxy to be a creditable confidant. Rex meanwhile is presented as cool and amiable, not a jealous husband easily riled. And the jazz-singing blonde (Marti Stevens) looks to be a hard-bitten babe of forty, rather than a dewy-eyed, clueless Desdemona.

If the story is creaky and unpersuasive, the script credit gives a hint why. The writer is one “Peter Achilles,” a pseudonym for blacklisted communist writer Paul Jarrico (alias Israel Shapiro). Jarrico seems to be making some point about the Hollywood blacklist, and betrayal, and false friends who “named names” to save their careers. But the “Othello” plot is a poor vehicle for such political agenda. Iago is a lousy villain to begin with, as he has no motive; while McGoohan’s version isn’t aiming at anything more nefarious than starting up his own jazz combo.

Fortunately the film doesn’t depend on this wobbly plot. The script is just a pretext to display the lavish production values in the film, and these are superb. The setting is an all-night music session, hosted by a jazz-loving toff (Richard Attenborough), who is celebrating Rex and Mrs. Rex’s wedding anniversary. The Canadian actor Bernard Braden has a broad turn as an irascible Jewish booking agent. He comes in, sits down, gets offended, leaves; his function in the plot being merely to raise the evening’s tension a few notches. This is an absolutely necessity, because for the first half of the movie everyone’s having a great time at the party, while the plot is going nowhere. Jazz notables on hand include the chubby, shy, polyglot Charles Mingus, who doesn’t have many lines but dutifully plucks his double-bass through much of the film. A goofily grinning Dave Brubeck arrives in a raincoat and heads straight for the piano, which he proceeds to play for twenty minutes while the camera shows us close-ups of his nimble fingers.

The set itself is a wonder, specially constructed to permit wide-angle shots and long camera takes throughout the building. Most Dearden films have no soundstages or special sets at all. They’re shot at outdoor locations, and in whatever cramped offices or houses happened to be available. But this cutaway film stage was intricately designed for this single production, and however wasteful and indulgent it may have been (the kind of thing Jerry Lewis or Orson Welles would do when they were in funds), it goes a long way to compensating for this early-60s jazz film disguised as pseudo-Shakespearean drama.

Jack Hawkins in The League of Gentlemen; Anthony Nicholls, Dennis Price and Dirk Bogarde in Victim.

The other two Dearden films in Criterion’s London Underground collection avoid racial matters. They have other lurid social issues to attend to. These are The League of Gentlemen (1960) and Victim (1961). League is a gentlemanly bank-heist film. It’s shot through with sophisticated comedy and, like a Rat Pack caper, has very nearly an all-star cast, beginning with retired colonel Jack Hawkins as the leader of the merry band. Then there’s the versatile Richard Attenborough again, no toff this time but a token oik who seems to be good with his hands; smooth Nigel Patrick once more, as a piss-elegant scrounger and former black-marketeer; and hoarse-voiced Richard Livesey as a fake clergyman with a long rap sheet for indecent behavior and related activities.

The ur-text for League is a familiar genre of war film: the kind where an assortment of brilliant scapegraces put together an escape from Stalag Luft. Only it is now ten or fifteen years after the war, and these ex-army officers are going to use their various specialties to escape poverty and abandonment by a society where they are misfits. One of our anti-heroes is a pathetic cuckold, another makes a living as a gigolo. The Nigel Patrick character goes broke while trying to run illegal gambling parties out of his flat, where the house never seems to win. (Period note: gambling casinos would become legal in London in another year or two.) The Attenborough character’s dark secret is that he passed secrets to the Soviets in Berlin, 1945—for money, not politics; and with the same mercenary motive he now rejiggers one-armed bandits for East End spivs. And then there’s a physical trainer and onetime Mosleyite named Captain Stevens, a presumptive homosexual who’s behind in his blackmail payments.

Actually the whole script is propelled by a kind of blackmail, since our Jack Hawkins colonel threatens to expose all his men’s dirt if they don’t cooperate in his little bank-robbery scheme.

So we have eight ex-officers in all, and they pull a double-heist. First they steal guns and explosives from an army base, posing as commandos from the Irish Republican Army. Then on to the main event: a bank near St. Paul’s, where someone has just delivered £1m in old, untraceable banknotes. Our gentlemen very nearly get away with it all. They get arrested at the end, thanks to the British Board of Film Censors. This is the film’s only wrong note. The bad ending hangs on an unlikely plot-point: it seems there was a little boy outside the bank, and he has a hobby of writing down out-of-town car license numbers.

Victim (1961), Dearden’s next major feature, is self-importantly noirish, much grimmer than the frolicsome League of Gentlemen. But visually, thematically, and in its tight, thrillerish pacing it feels like a sequel. Blackmail threats, only a background note of the earlier movie, here form the core of the plot. Once again we’re dealing with upper-middle-class professionals and others who are haunted by dark secrets in their past.

Supposedly the secrets in Victim are of the sodomite variety, but since there isn’t any sex or seduction in the film, I’d argue that the “queer” angle is really a convenient allegory for deviant politics, particularly those murky old spy-ring associations that would fascinate the London press for many decades. Films and serials about espionage and Cambridge Spy types would eventually congeal into a durable genre (Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy et al.). But we weren’t there yet in the early 1960s, so if you wanted to tell a story about dark rumors and illegal activity, you had to titillate with suggestions of perversion. The titillation worked a little too well in the American market, where most distributors wanted nothing to do with it, because Dearden refused to edit a scene where a policeman utters the word “homosexual.” For the next two decades, Victim gained an unwarranted reputation as a daring, “underground” piece of cinema, something that in the 60s and 70s would turn up as late-night fare on the art-house circuit. Gay film festivals discovered it in the 1980s and presented it as a kind of Stone Age plea for Gay Lib. (Meantime the star, Dirk Bogarde, used Victim to escape from his matinée-idol typecasting, and moved on to weirdo roles, e.g., in The Servant, The Damned, Death in Venice, and The Night Porter.)

Superficially, the plot of Victim revolves around a successful 40-year-old barrister, Melville Farr (Bogarde) who has taken it upon himself to expose a ring of blackmailers preying on mostly mature and well-heeled gay men. One of the blackmail victims is a businessman-peer, another a successful photographer, yet another a famous actor (performed by Dennis Price in a near-libelous caricature of Noël Coward). But our white-knighting barrister is soon shocked and baffled to discover that his blackmailed friends don’t feel particularly victimized. They’re happy to pay, as they are wealthy and welcome this extortion as protection money. And then we find that two of the key operatives in the blackmail ring are also “that way.” Nearly the only upright, honest man in the film is a seasoned old policeman, who doesn’t judge anyone’s sexuality, because he’s after real criminals. Cops are really the good guys, the script tells us. Whereas homos are sort of like rampaging Comanches, preying upon each other and everyone else.

Like Sapphire, Victim has suffered from superficial reading by inattentive critics. You will often read that the gay men here are upstanding innocents, and that the film presents them sympathetically. Obviously, from what I’ve just said, this is hardly the case. Furthermore, you’ll read that Farr himself (Bogarde) is a closeted homosexual who sacrifices his career by chasing the blackmailers. In reality the script tells us that married-man Farr hasn’t actually had any homosexual relationships (though he confesses to inclinations). Once upon a time, at university twenty years ago, there was a fellow student who became infatuated with Farr and, when rejected, killed himself. This supposedly is the great wound in Farr’s past. But it’s the merest ghost of a hint of personal scandal, about as compromising as an old rumor that you had Leftist friends in the 1930s, and they raised funds for the Spanish Loyalists.

Ultimately the film is a critique of social class. The upper-class characters have money and connections to buy their safety. The real victims are lower-middle- and working-class characters who impoverish themselves to pay the merciless blackmailers. Here is an obvious parallel between the film’s comfortable homosexuals and such Soviet spies as Philby and Blunt who were long protected by government and colleagues, and then rewarded with cushy jobs in art and journalism when their spook days were over. Meanwhile, the little lowly-born mice in the Soviet espionage apparatus were neatly rounded up by MI5 and packed off to prison.

* * *

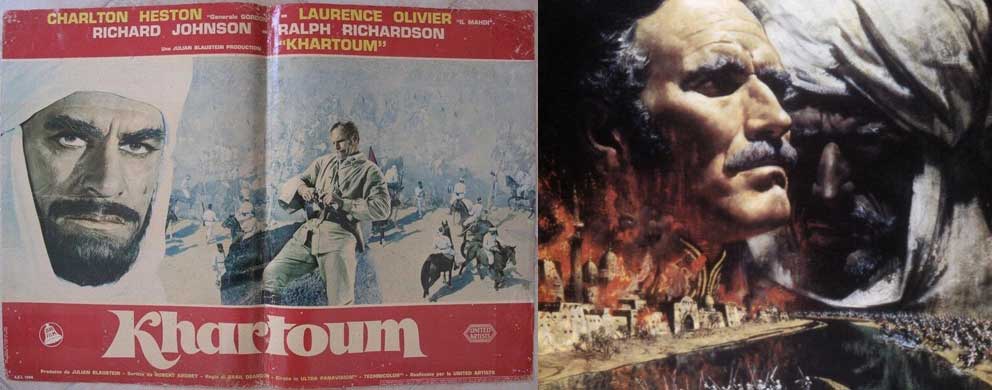

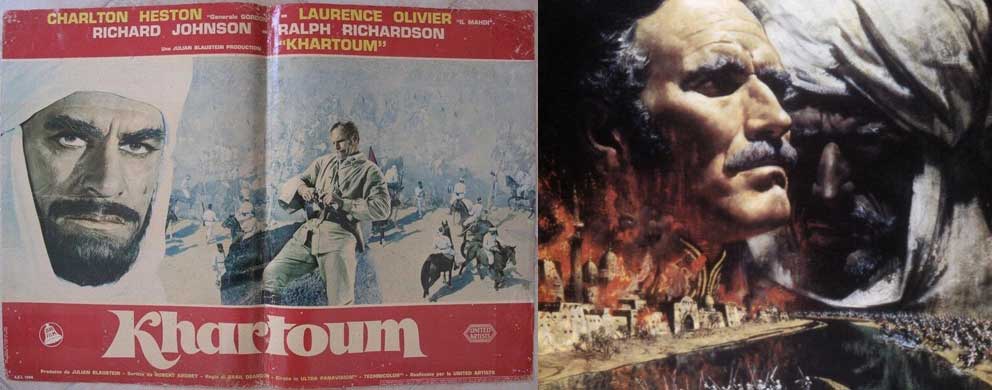

On a lighter note, I want to finish up by talking about Khartoum (1966), which is at once Dearden’s most uncharacteristic and “commercial” work. Well, maybe not that commercial. After opening to stunning reviews, it failed disastrously at the box office. Through the years it’s steadily sunk in critical esteem, in spite of—or because of—its intelligent script, its visual beauty, and its epic grandeur.

The great flaw in Khartoum is the casting of Laurence Olivier as Muhammad Ahmad, the great Mahdi, leader of a great jihad in 1880s Sudan. Nobody seems to have realized it at the time, but Olivier treated the whole project as a joke. He was one of the initial choices as co-star in 1962, when Khartoum entered development as a Lawrence of Arabia-style spectacular. He was then slotted to play opposite Burt Lancaster as General Charles “Chinese” Gordon. But time and commitments marched on: Lancaster dropped out, Olivier dropped out, and Charlton Heston came on board. By the time shooting was about to begin in 1965, Olivier was back in the cast, but he could only do a few scenes, and wouldn’t do them on location (which was Egypt, not Sudan, as Sudan was in upheaval again). So when the location shooting was finished, the main production unit moved to Pinewood Studios near London, and shot the Olivier scenes on a soundstage.

For some reason Olivier decided to do the Mahdi as high-camp comedy, with blackface, flamboyant gestures, and a comical voice. In many promotional stills and European posters, Olivier is wearing light-tan makeup and looks not unlike Alec Guinness as Prince Faisal in Lawrence of Arabia. On the film set, though, Olivier went for ultra-dark makeup, so that his face is an unrecognizable smudge. In fact, the first time I saw this film, I was close to the end before I realized that this clown in blackface was Laurence Oliver. Like Basil Dearden, Larry was there for the paycheck, not to be memorialized in what he must have regarded as an overblown, overproduced embarrassment.

Re-screening Khartoum in 2009, a critic in the Guardian commented that, “Just about everyone involved in this 1966 epic about Britain’s imperial adventure in Sudan deserves to have sand kicked in their faces.”

[Olivier’s] stab at a Sudanese accent sounds like Sebastian, the singing Caribbean crab from Disney’s The Little Mermaid, pretending to be a Russian spy. “Oh, beylovvids!” he says to his beloved followers. . . . Heston plays it straight, leaving Olivier looking even more like he has escaped from a racist panto.

Quite. But what the Guardian writer seemed to miss is that Olivier’s low-comedy turn was intentional. The difference between his “promotional” makeup and what he slapped on for the screen is, well, night and day. You have to think Dearden permitted these antics because he was too much in awe of the great Laurence Olivier.

Charlton Heston had no great regard for Basil Dearden as director; Dearden was a last choice, after Carol Reed and other directors refused the project. In this one instance, at least, maybe Heston’s judgment was right. Dearden couldn’t direct Larry. On the other hand, Heston could have complained about Olivier’s clownishness, and evidently did not. And so to this day, if you search out stills and posters for the film, you will find the Olivier character in a variety of hues ranging from Caucasian to deepest Shinola.

Today as in 1966, the Khartoum viewer is constantly reminded of Lawrence of Arabia. You have the lingering desert vistas, and hordes of savage Muslim tribesmen. There’s also a score by Maurice Jarre, and a very driven, confused central character. Instead of a mystical, fatalistic T. E. Lawrence played by a then-unknown Peter O’Toole, we have Heston as the mystical, fatalistic Gordon. Like Lawrence, Gordon is sent off on an exotic, vaguely defined mission, and like Lawrence he goes rogue in his own heroic and foolhardy way. Alas, he doesn’t get to return to England or die many years later in a motorcycle accident. He’s speared to death and ends up decapitated, with his head twirling atop a long pole in the final scene. And that’s not the most appalling scene in the film. (Someone thought the twirling-head bit was too gruesome, so it’s cropped out of TV and DVD editions.)

The trouble with Heston in the role is that he was already a familiar screen presence, so it’s hard to get engaged with the quirky character of General Gordon. When O’Toole did Lawrence of Arabia, nobody knew Peter O’Toole and few but the ancient remembered much about T. E. Lawrence (mainly from the lecture/travelogue show that Lowell Thomas and Dale Carnegie toured with in the early 1920s). So when O’Toole’s film came out in 1963, you got to meet Lawrence with fresh eyes. In Khartoum, you can’t stop seeing Charlton Heston, acting away with the same grim, perturbed mien we see in other roles of the period (whether in 55 Days at Peking or Planet of the Apes).

And yet, during its brief honeymoon of critical acclaim in 1966, Khartoum was widely praised, mainly for its cinematography and “very literate” screenplay by Robert Ardrey. A few people caviled about historical inaccuracies, but these were generally not Ardrey’s fault; they were things that needed to be inserted into the script for marketing reasons. The real Mahdi and Gordon corresponded but never actually met, although they do twice in the film. It simply would not have done for the co-stars merely to be pen-pals, when there were all those posters splashed around, showing them side-by-side and cheek-by-jowl . . . as though they were always trotting off together into the Ultra Panavision desert, like Omar Sharif and Peter O’Toole.

Notes

[1] David Thomson, 1980; quoted in Alan Burton and Tim O’Sullivan, The Cinema of Basil Dearden and Michael Relph (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), 2009.

[2] Victor Perkins, 1962; quoted by Meredith Taylor, in “Neglected British Film Directors: Basil Dearden,” in Filmuforia, 2018. Note: Mr Alan Price—not the musician but a writer and reviewer—has informed me that it was actually he, and not Meredith Taylor, who authored most of this Dearden appreciation. Indeed, I now see his byline at the very bottom of the Filmuforia essay though Meredith Taylor is named as author up top, possibly because she laid in the article. (WordPress has a workaround for this.)

Link: http://filmuforia.co.uk/underrated-directors-basil-dearden/

[3] Taylor (Price), Filmuforia.

Finally our hero has to go to work doing marketing for a fast-food franchisor, and he comes up with the idea of a Snagglepuss Chili Dog chain. He’s got a special way of cutting hot dogs so that when you grill them (or sauté them—he’s the kind of guy who in 1966 was saying sauté) they curl up into a wreath so you can serve them on hamburger buns, and put chili or other fillings in the doughnut-hole! Well he and some investors do set up a few low-budget Snagglepuss locations in Florida, and they do okay. Home of the Round Chili Dog! Only ten cents! Except they have to raise the price to 15c and then 20c. And he makes a couple of animated commercials for this local market. But then one of the franchising groups for Bob’s Big Boy buys out the big investors and replace the revolving Snagglepuss statue with the Big Boy.

Finally our hero has to go to work doing marketing for a fast-food franchisor, and he comes up with the idea of a Snagglepuss Chili Dog chain. He’s got a special way of cutting hot dogs so that when you grill them (or sauté them—he’s the kind of guy who in 1966 was saying sauté) they curl up into a wreath so you can serve them on hamburger buns, and put chili or other fillings in the doughnut-hole! Well he and some investors do set up a few low-budget Snagglepuss locations in Florida, and they do okay. Home of the Round Chili Dog! Only ten cents! Except they have to raise the price to 15c and then 20c. And he makes a couple of animated commercials for this local market. But then one of the franchising groups for Bob’s Big Boy buys out the big investors and replace the revolving Snagglepuss statue with the Big Boy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.